- Home

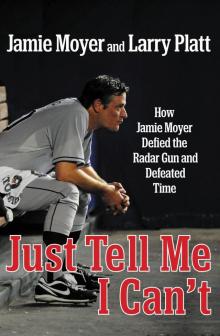

- Jamie Moyer

Just Tell Me I Can't Page 2

Just Tell Me I Can't Read online

Page 2

A great deal of talent is lost in this world for want of a little courage.

—Harvey Dorfman

As it was for many ballplayers, the idea of seeing a psychologist—a shrink!—was total anathema to Jamie Moyer. But there he was, on a crisp, sunny day, wandering the baggage claim area of Phoenix’s Sky Harbor International Airport, looking for his last and best hope at salvaging the only career he’d ever wanted. He was twenty-nine years old, with a wife and infant son at home, and he was without a baseball team for the first time since he was eight years old.

Back then, Moyer would tell whoever would barely listen that he was going to be a major league pitcher. There were plenty of doubters, even as he dominated in high school and college. But he’d made it to the Show, using the naysaying as psychic fuel along the way. But when the call came from Tom Grieve, general manager of the Texas Rangers, on November 12, 1990, how Moyer had always defined himself was suddenly no longer applicable. With six terse words—“We don’t see you helping us”—Jamie Moyer became a former big leaguer. And one with a desultory 34–49 career record.

Rock, meet bottom.

So Moyer thought, What do I have to lose? before flying to Arizona to meet someone his agent, Jim Bronner, thought could be of help. As Karen said before sending Jamie on his way, “Treat this as a learning experience.”

He was here to meet Harvey Dorfman, who was arriving on another flight. Together they would drive to Dorfman’s home in Prescott, Arizona, about ninety miles away, for a weekend of sessions that…what? Would have him unearth long-dormant resentments about his mother while he was lying on a couch?

In truth, Moyer had read and been intrigued by Dorfman’s classic book The Mental Game of Baseball: A Guide to Peak Performance, and he’d heard good things about Dorfman from players in the Oakland organization, where Dorfman was on staff and in the process of revolutionizing the subterranean world of sports psychology. But Moyer had grown up in the tiny blue-collar hamlet of Souderton, Pennsylvania, not exactly a New Age zip code.

Plus they weren’t a particularly emotive bunch, the Moyers. They expressed themselves through a shared love of baseball. Neighbors would pass the nearby ball field and see those baseball-crazy Moyers—mom Joan, sis Jill, and Jamie all in the outfield, shagging dad Jim’s fly balls. Jim, a former minor league shortstop, served as Jamie’s coach throughout American Legion ball. Souderton, a working-class suburban town of some 6,000 residents an hour outside Philadelphia, was where Moyer’s baseball education took hold—as well as his values. His early baseball journey was nurtured by an entire town that seemed to jump right out of some idealized version of America’s past; the same folks who cheered on his three no-hitters his junior year of high school populated Friday night’s football games and prayed together at church on Sunday. He’d gone from that atavistic world into the macho realm of the professional baseball clubhouse, where introspection is traditionally looked upon with suspicion.

“Hi, I’m Harvey Dorfman,” a waddling, croaky-voiced fiftysomething said, approaching with outstretched hand. Dorfman didn’t look like an athlete, with his hunched shoulders, gimpy gait, and baggy sweatshirt, but Moyer knew that during the season he was in the dugout in an Oakland A’s uniform. And anyone—even a shrink—who wore the uniform deserved the benefit of the doubt.

On the awkward ride to Dorfman’s house, the two men made small talk. Dorfman asked open-ended questions about Moyer’s upbringing and his history in the game, and soon Moyer was unburdening himself:

“I can’t throw my curveball for strikes.”

Dorfman said nothing.

“I got to the major leagues because of my changeup, but I just show it now. I don’t throw it for strikes.”

Dorfman said nothing.

“When I’m on the mound, I can’t stop thinking about being pulled. Or released.”

Dorfman said nothing. He simply smiled.

Isn’t this guy going to tell me what to do? Moyer wondered.

A few months before Moyer’s pilgrimage to Prescott, Saturday Night Live broadcast an uproarious skit featuring guest host Michael Jordan. Called “Daily Affirmations with Stuart Smalley,” it was a classic send-up of what happens at the intersection of self-help culture and jockdom. Al Franken played Smalley, a cable TV host described as a “caring nurturer” and “member of several twelve-step programs,” who was looking to provide gentle encouragement to “Michael J.,” an anonymous basketball player.

Jordan is coaxed into admitting that sometimes before big games he gets nervous. Smalley tells Jordan to look in the mirror and quell those “critical inner thoughts” by reciting his daily affirmation: “I don’t have to dribble the ball fast, or throw the ball into the basket. All I have to do is be the best Michael I can be. Because I’m good enough, I’m smart enough, and doggone it, people like me!” The skit ends with a hug between the best athlete in the world and this comical, cliché-ridden would-be therapist.

Harvey Dorfman was the real-world anti–Stuart Smalley. He knew that the calm, nurturing counselor, with that soothing NPR voice, was a total nonstarter in sports. Unlike other sports psychologists, he knew he had to have a macho persona in order to break through to the modern-day athlete. Even though Dorfman was a bibliophile who could deconstruct the novels of Somerset Maugham in great detail, ballplayers just knew him as a foulmouthed taskmaster. “I don’t care about your feelings,” Dorfman would tell them. “I care about what you do.”

The character of SNL’s Stuart Smalley was everything Dorfman disdained about those in his own profession: too precious, too solicitous. But the skit did nail the crisis in confidence world-class athletes inevitably face. Dorfman had had a procession of major league ballplayers walk through the door to his study over the years, all doing battle with their internal demons, all—no matter the runs batted in or hitters fanned—feeling like, as Smalley would say, imposters. Dorfman knew, of course, that they weren’t imposters—just works in progress. But try telling that to an athletic prodigy who, through achingly dull repetition, is raised to train his muscle memory so that the physical act becomes something done by rote. Without fail, ballplayers—and for that matter the wider, retro world of baseball—had never contemplated the possibility that the same type of discipline might be needed to train the mind, so its overactive chatter could get the hell out of the muscles’ way. Dorfman adopted an in-your-face persona, more tough-love coach than shrink, designed to jump-start his clients into awareness and action. As he’d tell them, “Muscles are morons. Self-consciousness will screw you up.”

Not exactly Freudian wisdom. But then Dorfman wasn’t even a shrink. No, he’d been a high school English teacher and basketball coach at Burr and Burton Academy in Manchester, Vermont, where he coached the girls’ team to a state title. He was equal parts jock and man of letters, as likely to quote Shakespeare as to dissect the virtues of the two-hand chest pass. He contributed columns to the local paper, slice-of-life profiles of local characters. A baseball column he penned for the Berkshire Sampler led him to profile minor leaguers on the Pittsfield Rangers, a Double A farm team of the Texas Rangers. He and top draft pick Roy Smalley sat for hours, sharing psychological insights. Smalley, who had attended the University of Southern California, recommended the book Psycho-Cybernetics, by Maxwell Maltz. When Dorfman indicated he’d already read and liked the book, Smalley knew he’d found a kindred spirit.

Once he made the Show, Smalley introduced Dorfman to Karl Kuehl, a coach with the Minnesota Twins. Kuehl, who passed away in 2008, had noticed that players excelled when they were able to simply stay in the moment and set aside their doubts and fears. Dorfman partnered with Kuehl in researching the mental side of the game, and the two began working on a book that would become the bible of sports psychology. The Mental Game of Baseball was published in 1989, and dog-eared copies fast became a staple in baseball clubhouses throughout the major and minor leagues.

When Kuehl became the Oakland A’s farm director in 1983, he pe

rsuaded general manager Sandy Alderson to hire Dorfman. Alderson, as documented by Michael Lewis in Moneyball, would later take on the baseball establishment by playing a critical role in the embryonic stages of the sabermetric revolution. A former Marine and Harvard Law grad, Alderson didn’t come up through the baseball ranks and was wired to challenge the game’s conventional wisdom. Putting Dorfman in uniform, placing him in the dugout, and making him responsible for, as Harvey put it, everything above the shoulders on every player was a move ahead of its time.

The same could be said of Dorfman’s theories. In the last decade, the science of the mental side of sports has become a popular topic among the intelligentsia. In 2000, the New Yorker’s Malcolm Gladwell wrote an article entitled “The Art of Failure.” In it, he defines “choking”—the worst kind of athletic failure—as the opposite of panic. He might as well have been quoting Dorfman from the 1980s. “Choking is about thinking too much,” Gladwell writes. “Panic is about thinking too little.” In 2012, writer Jonah Lehrer cited in Neuron a study by a team of researchers at Caltech and University College London, in which escalating monetary rewards were offered to players of a simple arcade game. As the stakes got higher, player performance significantly worsened.

Intellectuals like Gladwell and Lehrer buttressed their writings with reports from the front lines of neuroscience research, which had become all the rage, but their findings echoed Dorfman from the ’80s. Only Dorfman didn’t need to don a white coat in order to discover the degree to which self-consciousness altered athletic outcome. His laboratory was Major League Baseball itself, and after Alderson gave him the opportunity, the ensuing years found him developing his unique approach and putting his theories into practice.

There was, for example, the mano a mano with Jose Canseco in the minors, after the phenom failed to run out a grounder. There Dorfman was, right in the slugger’s face after Canseco nonchalantly shrugged off his lack of hustle by chalking it up to “normal” frustration.

“Normal?” Dorfman shrieked. “You want to be normal? You’re an elite athlete. You’re already exceptional—and that’s what you should want for yourself. To be extraordinary, not ordinary.”

Canseco, backing down, asked how he should have handled his emotions. “Just train yourself by saying, ‘Hit the ball, run. Hit the ball, run. Hit the ball, run,’” Dorfman explained. “It’ll become an acquired instinct. It doesn’t matter how you feel during combat; you fight.”

Just a year and a half prior to Moyer’s visit, Dorfman had been instrumental in settling down A’s pitcher Bob Welch. Welch, a recovering alcoholic, had always been a jumble of nerves, fidgeting on the mound to the point of distraction, especially when the pressure mounted. “You can make coffee nervous,” Dorfman told him. Welch would become frenetic on the mound, in a rush to get the ball back from his catcher. Dorfman and catcher Terry Steinbach conspired together. When Welch would walk to the front of the mound, waving his glove in order to get the ball returned—now!—Steinbach wouldn’t throw it. That, Dorfman told his pupil pitcher, would trigger the signal in Welch’s mind to take a deep breath, exhaling slowly, bringing himself down.

To the ballplayers, Dorfman was as in-your-face as the other coaches, it’s just that he provided practical mental tips. Welch joked, “If you told Harvey you just killed somebody, he’d say, ‘What are you going to do about that?’”

Dorfman’s emphasis on practical tactics was an actual psychological school of thought he was the first to apply to baseball: semantitherapy. Freudians, Dorfman believed, in their search for the long-dormant cause of a patient’s fear or neurosis, forgot to treat the manifestation of those fears. Perhaps the root of a fear of flying is in a patient’s childhood in the form of a long-ago traumatic experience. But just as real are the current-day sweaty palms and heart palpitations as the plane readies for takeoff. In baseball, Dorfman realized, if you conquer the symptoms, you kill the disease.

Now this kid Moyer presented with some familiar indications. Fear, doubt, lack of confidence, distracting thoughts. For the better part of three days, Dorfman would give the kid the full treatment. He and Anita, Dorfman’s wife of thirty-one years, a schoolteacher who’d grown used to and welcomed these visits from shy, awkward athletes, lived in a house at the top of a hill on a secluded cul-de-sac. He and Moyer would do multiple two-hour sessions in Dorfman’s study each day, go for long walks in the Arizona hills, and have breakfasts of oatmeal and bagels with Anita. Dorfman didn’t usually work with players who weren’t in the A’s system, but this was a favor to Moyer’s agent, Jim Bronner. The kid was nearly thirty and had a losing record. There was a lot of work to be done.

At least there’s no couch, Moyer thought, entering Dorfman’s study. Dorfman settled in behind a big oak desk, in front of a bookcase that housed many of the inspirational quotes and anecdotes that Dorfman would pepper his life lessons with. Moyer would hear those gems over the next twenty-odd years; they’d seep into his consciousness much like Harvey himself, everything from Cromwell’s “The man who doesn’t know where he’s going goes the fastest” to Marcus Aurelius’s “If you are distressed by anything external, the pain is not due to the thing itself but to your own estimate of it; and this you have the power to revoke at any moment.”

Moyer didn’t know what was in those books, and he didn’t know what to think. He was about to pick up the conversation where he’d broken it off in the car—with a recitation of all that he was doing wrong—when Dorfman lurched forward.

“There are a couple of things you need to know, kid,” Dorfman said. “First, this doesn’t work if you’re not honest with me. I don’t have time for you if you’re not going to level with me. And second, none of this goes back to your agent or your club or the media. This is just you and me.”

Just you and me. The words washed over Moyer. The mound, once a calm escape, had become frightening in its solitariness. On it, he was keenly aware of them: the fans, the manager, the teammates. He’d hear them, or he’d imagine what they were thinking about him. When a fan heckled him for his lack of speed, he’d carry on an angry pretend dialogue in his head: You think this is easy? When runners got on, he’d wonder what his teammates were thinking, he’d decipher the body language of his catcher—was he against me now too? He sensed—or invented—collective doubt all around him, and it led him to wonder, Do I belong? But now here was someone who actually wore a major league uniform saying he was there with him.

Moyer returned to his narrative, cataloging all that he can’t do on the mound. Can’t get ahead of hitters. Can’t throw the changeup, once his money pitch. Can’t stop furtively glancing into the dugout to see if the skipper is on the phone to the pen. He talked about how the middle twelve inches of the seventeen-inch plate belong to the hitter, but how the umps rarely consistently gave him what he believed to be rightfully his: the outer inches on either side. Finally, Dorfman, who’d been listening with his eyes locked on Moyer’s, had heard enough.

“Bullshit.”

Pause. “Excuse me?”

“Bullshit. You have control over that. Over all of it.”

“I do? How?”

“By changing your thought process. You gain control over all of it by acknowledging that you have no control over any of it, the umpire, or the manager, or what other people think, and by taking responsibility for what you can control.”

Moyer wasn’t getting it. “Are you aware of how you talk about yourself?” Dorfman asked. “It’s all negative. ‘I can’t, I can’t, I can’t.’ I’ve seen your act, kid, and you need to get better. You need to change your thinking. Your process needs to be positive. You have to train yourself to hear a negative thought, stop, let it run its course, and then let it go. ’Cause it doesn’t mean crap. The only thing that matters is focusing on the task at hand, which is making that pitch. The task at hand.”

It’s a page right out of classic Zen meditation—stop, label the distracting thoughts, and return to your breath. Dorfman reminde

d Moyer of one of baseball’s most infamous cases of the yips, when Dodgers second basemen Steve Sax suddenly, inexplicably could no longer make the rudimentary throw from second to first. If, when Sax fielded the ball, he thought to himself, I’m not going to throw this ball away, he might have thought he was thinking positively. But he was actually focusing his mind on committing an error—in effect, directing his body to do just that. A better thought, Dorfman explained, would be, I’m going to hit the first baseman with a throw that’s chest high.

To get there, though, the player has to learn to think about what he’s thinking. To reformulate his thoughts. Dorfman suggested an exercise. “I want you to rephrase everything you’ve already told me, taking out all the ‘can’t’ stuff, all the negativity. Restate it. Go ahead. I challenge you.”

This is going to be hard, Moyer thought. How do you positively observe that you can’t throw your curveball for strikes? He stammered and stuttered, started and stopped. Finally, he came to this: “I’m going to throw a sweeping curveball that catches the inside corner to a righthanded hitter.”

Dorfman seemed pleased. But, he said, just stating that isn’t enough. “You need to see it,” he said. “You need to visualize the flight of that curveball before you throw it. So you say it, you see it, and then you throw it.”

In this way, Dorfman explained, the mind was as much a muscle as any other on the pitcher’s body: “We’re training it.”

Moyer’s own idol, Steve Carlton, was the master of such training. Carlton considered pitching nothing more than a heightened game of catch between him and his catcher; the batter was merely incidental. On days that he’d pitch, Carlton would lie down on the training table after batting practice and close his eyes. Teammates would laugh, thinking he was napping. In reality, he was imagining his “lanes” in the strike zone—an outer lane and an inner lane. He’d imagine the flight of his ball within those lanes, over and over. The middle of the plate didn’t exist in his mind’s eye, and nor did any menacing hitters or rabid fans. He was fixated on those lanes. He was focused, as Dorfman would say, on “the task at hand.”

Just Tell Me I Can't

Just Tell Me I Can't